This photo is a recent acquisition, part of a small lot of photos from Norway. I took one look at it and thought: “That looks like France” – the countryside is decidedly not Norwegian. The thing that really tipped me off was the helmet carried by the guy on the right, which sports the camouflage paintjob seen on helmets worn by troops stationed in Normandy. Then I flipped the photo, and saw a scrawled note on the back with “Caen” in it. Bingo! Further analysis of the photo makes me pretty sure that the soldiers belong to a Luftwaffe Field Division, things like the cap worn by the soldier on the right, and the belt buckle on his comrade on the left. That, and the location, tells us that only one unit can come into question: The 16. Feld-Division (L).

The 16. Luftwaffen-Feld-Division was formed in December 1942 by the XIII. Fliegerkorps. It was transferred to the Heer (Army) in November 1943 and redesignated 16. Feld-Division (L). It was deployed in the Hague-Haarlem area of the Netherlands as an occupation force. In June 1944, the division was sent to Normandy under the control of Heeresgruppe B and deployed in the front lines on 2 July. The British launched an offensive the day after the division arrived and by late July, it had been effectively destroyed in the defense of Caen. The division was formally dissolved on 4 August 1944, its remaining infantry allocated to the 21. Panzer-Division, while other elements were used to resurrect the 16. Infanterie-Division. (More on the Luftwaffe Feld-Divisionen here.)

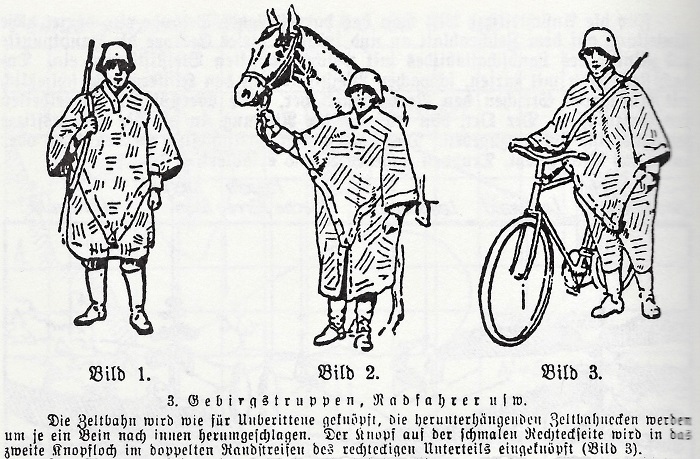

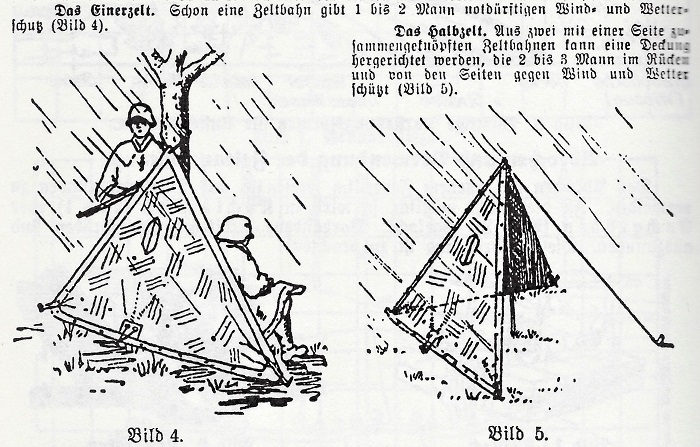

Some more observations on the guys in the photo: the one on the left has a leather map case, binoculars (probably 7×50), a magazine pouch with three magazines for his MP 40 (not visible), and a helmet possibly painted with a mix of dark yellow paint and sawdust (to reduce glare). His colleague wears a Zeltbahn as camouflage, 6×30 binoculars, and probably an MP 40. Both are NCOs, as there are no rank insignia on the sleeves.

Speaking of Normandy and the Allied landings there, this year marks 20 years since the premiere of Saving Private Ryan, the epic war movie directed by Steven Spielberg. Regarded as one of the great war movies, I’m not quite as impressed by it. While there are some powerful scenes in it, like the brilliantly staged beach landing, the movie has several weak spots. I’m not going to nit-pick on trivia like the fact that there were no Tiger tanks in the American area of Normandy by the time the action takes place, but I’ll address problems with the plot.

The basic premise of the movie is that it is discovered that all brothers Ryan are killed or missing in action around the same time. Mommy Ryan receives all the telegrams just a few days after the D-Day landings. By that time, most of the airborne units were still struggling to organize themselves after being scattered over a large area. In real life, it would’ve taken many days, if not weeks, before it would’ve been apparent that Private Ryan was indeed MIA. In the movie, the rescue operation is launched just a few days after D-Day.

One pivotal scene is when Captain Miller (played by Tom Hanks) decides that it’s important to knock out the German defenders of a damaged radar installation. The squad charging uphill against a machine gun position, the medic, Wade, is mortally wounded. Miller had a crack sniper, Jackson, in his squad – why not take out the MG crew at a distance? Or just bypass the Germans, as they weren’t a threat? The whole scene is just a way of introducing the surviving German soldier, “Steamboat Willie”, and setting the stage for the final scenes.

After finding the right Ryan, the surviving members of the squad (plus some airborne troops) are pitted against crack Waffen-SS troops in the fight for the fictious town of Ramelle. The Germans make just about every tactical mistake they could make; even considering the state of German troops by that time of the war, they wouldn’t have assaulted a town like that. Anyway, in the fighting, most of the squad meets a sticky end, including Captain Miller, who is shot by “Steamboat Willie”. “Willie”, who was let go by Miller earlier, and who has been picked up by the SS unit, clearly doesn’t know who he’s firing at. The interpreter, Upham, kills “Willie”. This is one of the morally ambigious problems with the story. Was Miller wrong to let “Willie” live? Should they’ve killed him straight away, the only good German being a dead German? Spielberg didn’t think this through, obviously.

Upham and Ryan are the only survivors, and the final scene has an aged and tearful Ryan by the graves of Miller and the others, surrounded by his family. Seven men died so he could live. Was it worth it? Mommy Ryan got one son back, and he apparently raised a fine family, but seven other mothers lost their sons, men who never got to form families and raise their kids. The movie leaves that question open, but I for one find that it’s debatable whether it was worth the sacrifice. The whole plot feels contrived, but at least Spielberg and Hanks got the inspiration to make “Band of Brothers”, that most excellent mini-series.