In an office in the city hall of Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Major Wilhelm Wagner writes his name in “the Golden Book”, a tome dedicated to important visitors and prominent citizens. He has been awarded the coveted Ritterkreuz – the Knight’s Cross – for his leadership during the heavy fighting on the Eastern Front. His hairline makes him look older than his 28 years, but this was a time which could age men prematurely. Wagner was born in Ludwigshafen on 8 September 1915. He grew up during the tumultuous years following the First World War, political unrest and economic hardship influencing his childhood and teens, and joined the Reichswehr when it was about to expand after Hitler’s rise to power. Not very much is known about him other than his military service, and it appears like he had a quiet life after the war, probably a civilian career after release from a Soviet prisoner of war camp in the early 1950s.

The photo was part of a lot I bought on eBay, and as usual, the good members of the Axis History Forum helped me in identifying the man and to decipher the scrawl on the back. It says:

Major b. Eintrag ins Gold. buch

der Stadt Ludwigshafen/Rh.

It seems like his branch of service was the artillery, and that he served at the front from at least the start of Operation Barbarossa. He was awarded the Iron Cross, 2nd and 1st class. As Oberleutnant (1st Lieutenant) in II. Abteilung/Artillerie-Regiment 129 of the 129. Infanterie-Division, he must’ve made quite an impression, as he was awarded the Deutsches Kreuz in Gold on 10 February 1944. It was probably for acts during 1943, as he appears to have risen in rank during the winter of 1943-44. Sometime during this time, he was promoted to Hauptmann (Captain), and transferred from the 129. Infanterie-Division to the 58. Infanterie-Division in Army Group North, where he became the commanding officer of II./Artillerie-Regiment 158. There was a lot of heavy fighting along the front, and the Artillerie-Regiment 158 wasn’t spared:

The heavy defensive and retreat battles continued until mid-January 1944 and ended in the Ssweblo Lake area. Here the regiment could catch a breath before moving to Pleskau at the end of January in order to secure the Luga-Pleskau retreat road. Heavy forest battles occurred north of Pljassa and Strugi-Krassyje. The 58. Infanterie-Division was encircled and had to fight its way divided into battle groups. The artillery regiment reassembled in the Wesenberg area and was refreshed. The regiment’s bicycle company was disbanded in February 1944. The regiment was reinstated in February 1944. The regiment arrived to Tallinn, where it served as a reserve unit for various divisions.

It was during this bitter fighting that Wilhelm Wagner showed courage and leadership, enough to earn him a recommendation for the Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes. He was awarded the medal on 11 April 1944, and it appears like he was promoted to Major at the same time. Wagner also got leave to visit his home city, where he signed the Golden Book. The remaining twelve months saw the Division involved in heavy defensive fighting, until it was destroyed in April 1945. Some troops managed to escape to the West, but the majority of the survivors went into Soviet captivity.

Wilhelm Wagner passed away aged 78 years on 4 July 1994 in Grünstadt, just west of Ludwigshafen.

Thanks to Axis history Forum members Ruslan M, nichte and Hohlladung for invaluable help in the preparation of this post.

Some reddish hues that shouldn’t be there, but not too shabby.

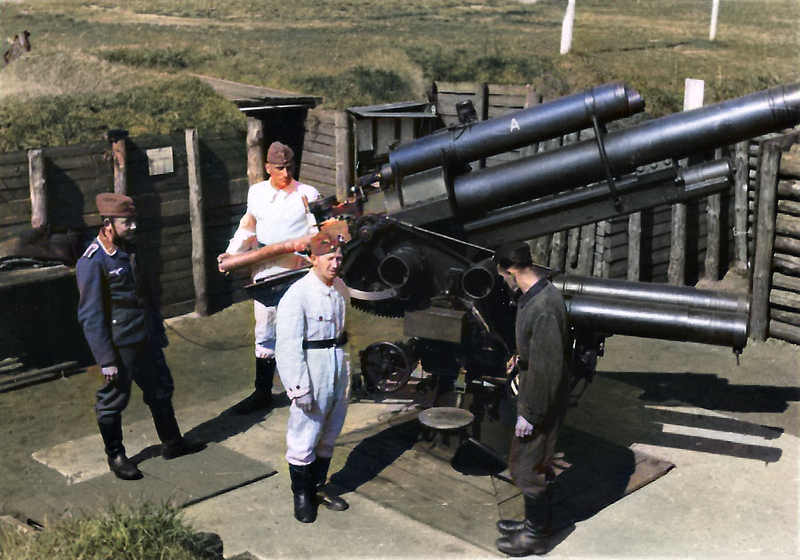

Some reddish hues that shouldn’t be there, but not too shabby. Here, the grey hues of mid-war uniforms have translated well.

Here, the grey hues of mid-war uniforms have translated well. The rusty brown of a burned-out tank is probably the best thing with this photo.

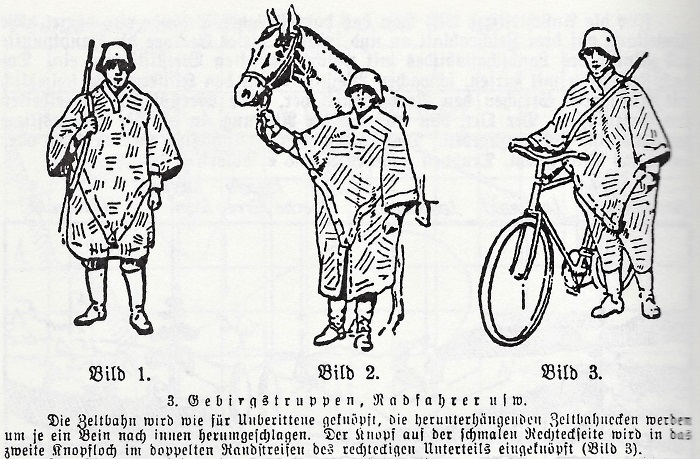

The rusty brown of a burned-out tank is probably the best thing with this photo. I love how the software managed to capture the different colors of the Zeltbahnen.

I love how the software managed to capture the different colors of the Zeltbahnen. The original photo for comparison.

The original photo for comparison. The brown hue on the caps is off, but otherwise it’s pretty good.

The brown hue on the caps is off, but otherwise it’s pretty good. This one turned out really nice.

This one turned out really nice. Looks almost like it’s an original color photo.

Looks almost like it’s an original color photo.